My LAL-D Journey

A 37-Year Path from Diagnosis to Breakthrough

My LAL-D Journey

A 37-Year Path from Diagnosis to Breakthrough

In the early 1980s, my family—originally from Iran—relocated to Kuwait in search of safety from the escalating Iran-Iraq conflict. As the eldest of five children, I witnessed firsthand the strength and resilience of my parents, who were close relatives, as they worked tirelessly to provide stability. In 1985, just after my youngest sister was born, she began experiencing frequent febrile seizures. Local doctors in Kuwait, alarmed by her enlarged liver and abnormal lipid levels, suspected liver cancer and recommended a biopsy. Faced with uncertainty and vague communication from the medical team, my parents made the difficult decision to seek answers in the United States.

Despite having built a comfortable life in Kuwait—our home, thriving business, and private schooling for all of us—the U.S. Embassy granted tourist visas to all seven family members. We arrived in Tucson, Arizona, in the summer of 1987 and stayed with a long-time family friend. What was meant to be a brief visit became a pivotal journey in our lives.

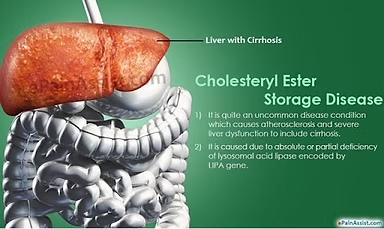

After undergoing a series of medical evaluations and a liver biopsy at University Medical Center in Tucson, both my sister and I were diagnosed with a rare genetic disorder: Cholesterol Ester Storage Disease (CESD), now known as Lysosomal Acid Lipase Deficiency (LAL-D).

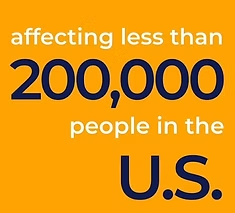

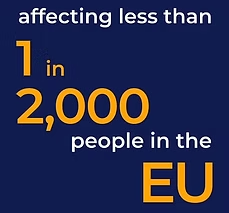

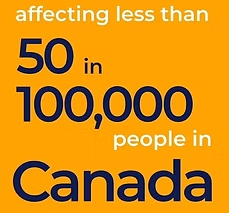

LAL-D is a chronic, inherited condition that severely impairs the body’s ability to produce Lysosomal Acid Lipase—an enzyme vital for breaking down cholesterol esters and triglycerides in the liver. Without it, the body accumulates toxic levels of fat in the liver and other organs. As an autosomal recessive disorder, LAL-D can lead to high cholesterol, early-onset cardiovascular disease, liver dysfunction, cirrhosis, and, in some cases, the need for a liver transplant. At the time of our diagnosis, only 30 documented cases existed worldwide. Today, estimates place its prevalence between 1 in 40,000 and 1 in 300,000 individuals, according to the NIH and the National Library of Medicine.

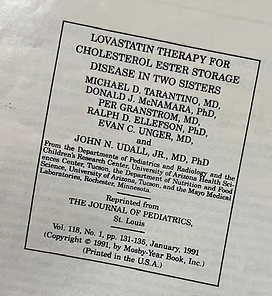

At just four years old, my sister—and I, then seventeen—quickly realized our “summer visit” to the U.S. was evolving into something much greater. Our case became part of medical history when we were featured in the Journal of Pediatrics in January 1991, as early recipients of treatment with Lovastatin—the very first statin drug approved in the U.S. I vividly remember translating complex consent forms for our mother, enabling the initiation of statin therapy in pediatric patients.

This was groundbreaking. Statins were traditionally reserved for adults, but in our case, they significantly reduced lipid levels and cardiovascular risk—offering a non-invasive alternative to the liver transplant that once seemed inevitable. It was a major relief for our family, and a pivotal moment in pediatric treatment for rare lipid disorders.

Our story attracted attention from the Tucson community and beyond. Local news outlets, including KGUN-9, covered our progress. Dr. John Udall—then Chief of Pediatric Gastroenterology at University Medical Center, and nephew of Arizona Senator Morris Udall—voiced hopeful predictions in 1988 about emerging treatments. He envisioned enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) as a future option: infusions that could restore liver function, balance lipid levels, and reverse fatty liver disease.

At the time, I was doubtful. Funding for rare diseases seemed unlikely amid national priorities like cancer and heart disease. Yet, Dr. Udall’s vision planted a seed of hope. My sister and I were the only known LAL-D patients in Tucson—and perhaps, the first ripple in a much larger wave of innovation to come.

I pursued a career in pharmacy, earning my Pharm.D. from the University of Arizona in 1997 and completing my PGY1 Pharmacy Practice Residency at Presbyterian Hospital in Albuquerque, New Mexico in 2000. Throughout my academic and early professional years, I strictly followed a low-fat diet and managed my lipid levels through prescribed medication.

During my pregnancy, I was classified as high-risk due to elevated lipid levels, which required me to pause all medications for nine months. My son was born in December 2010 at University Medical Center in Tucson. Although I couldn’t breastfeed due to the resumption of lipid-lowering medications, I was relieved to learn that he did not inherit LAL-D.

As an adult, I managed high lipid levels using a combination of oral and injectable therapies. Over time, I consulted multiple specialists—cardiologists, endocrinologists, gastroenterologists, and hepatologists—as my condition progressed. My liver enzymes rose, and I developed non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Despite disclosing my LAL-D diagnosis, many providers remained unfamiliar with the condition and its evolving treatment options.

In 2014, I connected with a geneticist at University Medical Center who enrolled me in the ARISE clinical trial, designed to evaluate a new treatment for LAL-D. I received bi-weekly infusions, but after limited improvement in my lab results—likely due to being in the placebo group—I parted ways with the provider.

In early 2021, I was referred to a renowned Tucson-based gastroenterologist specializing in liver disorders. We discussed my LAL-D and diabetes diagnoses. He affirmed my current medications and recommended lifestyle changes, also offering complimentary fibroscans of my liver every six months at his adjacent research center. While I followed through on the scans and updated my primary doctor, the specialist failed to follow up between 2021 and 2023. During my latest visit, a research assistant suggested I join a study, which I respectfully declined.

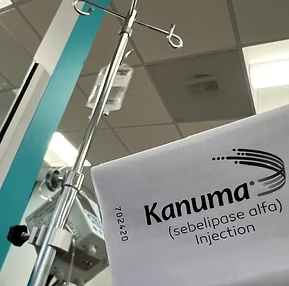

It wasn’t until November 2023 that I met Dr. Neda Ebrahimi, an endocrinology fellow at Banner Health. She took special interest in the link between LAL-D, fatty liver, and my increasingly complex diabetes management. As someone with a family history of diabetes and long-term statin use, I appreciated her attention to detail. While studying for her board exams, Dr. Ebrahimi discovered an FDA-approved enzyme replacement therapy for LAL-D: Kanuma, developed by Alexion Pharmaceuticals and launched in December 2015.

I was both surprised and thrilled. Kanuma is administered bi-weekly and offers a lifelong solution for patients with LAL-D. Dr. Ebrahimi and I immediately began coordinating with Alexion and my insurance provider to seek approval.

On March 6, 2024, I received my first Kanuma infusion—a full-circle moment, fulfilling Dr. Udall’s 1988 vision. After just two infusions, my liver function tests (LFTs) normalized and my HbA1c improved—marking a profound breakthrough. Today, after four and a half months, my labs show no signs of hyperlipidemia or elevated liver enzymes, as if Kanuma has reset my body.

Through Facebook, I’ve connected with a global community of LAL-D patients across all ages. These connections have been instrumental in learning about real-life Kanuma experiences. Due to my small veins, I was advised to use a power port for bi-weekly infusions—a small but vital change that eased my treatment routine.

Dr. Ebrahimi presented my case and Kanuma treatment as a poster at the Endocrine Society’s June 2024 conference in Boston, where it was nominated for a presidential award. The city holds personal significance—it’s where our original LAL-D diagnosis was confirmed in 1988 from blood samples and my sister’s biopsy.

Reflecting back to our brief 1987 summer medical trip, I now realize it was a turning point that led to accurate diagnosis and—decades later—effective treatment. I’ve always believed my role as a pharmacist goes beyond traditional settings. I am now committed to raising awareness of LAL-D, using media to amplify this message.

Though we had a confirmed diagnosis, many providers dismissed or misunderstood our condition. I pray for those still undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Unfortunately, my insurer recently questioned the diagnosis due to treatment cost. However, additional genetic testing re-confirmed my LAL-D. As I face possible job transitions, I now worry whether insurance will continue to cover this life-saving medication.

It’s been frustrating to learn that the liver specialist I once trusted never explored Kanuma as a treatment. Despite years of fibroscans, he failed to suggest or research solutions. When I finally saw him again in July 2024, he admitted being unaware of treatment options and had since semi-retired into research. I was deeply disappointed—he had attended multiple national conferences, yet knew nothing of Kanuma.

That oversight possibly cost me years of liver treatment, even as my diabetes worsened. I told him: even one patient with a rare disease deserves their doctor’s full attention and up-to-date knowledge. Testing and trial invitations alone are not enough. This moment was a sobering reminder of our healthcare system’s gaps—and a missed opportunity that took eight years to correct.

On August 16, 2024, our story aired again on KGUN-9 News in Tucson—the same station that covered our Lovastatin treatment in 1990. We used this opportunity to raise awareness of rare genetic diseases for patients and professionals alike. I also discovered my 2014 participation in the ARISE study helped lead to Kanuma’s FDA approval in 2015.

Alexion Pharmaceuticals has since recognized me as the first patient in Tucson to receive Kanuma. Dr. Ebrahimi is the first physician in the region to administer it. My sister is scheduled to begin her own treatments soon. I’m forever grateful for these milestones and Dr. Ebrahimi’s proactive, compassionate care.

To Physicians: Listen deeply. Stay informed. Rare does not mean irrelevant—every patient matters.

To Patients: Never lose hope. Medicine evolves. Pray. Fight. Learn. Advocate. Our 37-year journey from diagnosis to treatment is a testament to faith, science, and unyielding perseverance.

Shaida Namazifard, Pharm.D.

@yaasoanar_dr.Shaida | @shamdoney_dr.Shaida

yaasoanar@gmail.com

www.yaasoanar.com